Hello 👋

Welcome back to another edition of Weekend Rounds!

Well, this week was Groundhog Day. A day where we throw all science out the window and rely on a groundhog to determine if it will be an early spring or not. It’s not the silliest thing we do (looking at you annual White House turkey pardon), but it’s up there.

For the uninitiated, Groundhog Day is effectively this: if it’s sunny, a groundhog emerging will see its own shadow, get scared, and return underground - indicating 6 more weeks of winter. If it’s cloudy, then the groundhog won’t be spooked and will hang out for a bit which of course means an early spring. It’s also a fantastic 1993 comedy staring Bill Murray.

But it’s not the original prognosticator, Punxsutawney Phil, who gets to give an opinion. Apparently there are 32 groundhogs across the US and Canada who we now look to for a prediction. And it’s not just groundhogs either… there are 43 ‘alternative groundhogs’ including a lobster, an opposom, an armadillo, a peking duck, and multiple (multiple!) taxidermied groundhogs. Here’s a map of them all.

So do the predictions work? Well… not really. Apparently since 1969 Punxsutawney Phil has a success rate of about 39%. Which isn’t great if you’re trying to predict something since it’s literally worse than a coin flip. But a .390 batting average gets you into the MLB Hall Of Fame, so be kind to Phil.

However, some animals actually can be counted on for seasonal predictions. Phenology is the study of how seasonal events in the lives of plants and animals shift according to the weather and climate. And some of these patterns can help predict seasons, such as how fish or migratory birds respond to the temperature of water and air.

One thing for certain is that Groundhog Day is a North American tradition. To our wonderful readers across the world: is there an equivalent in your country or is this foolishness reserved for us?

Here’s what other (non groundhog related) stories we’re covering:

💸 The rising cost of pet care

👀 Seeing what animals see

🦇 What’s going on with the bats in San Antonio?

🚀 Quick hits

💸

The Rising Cost of Pet Care

A worrisome trend in our profession took center stage this week: how inflation, private equity and vet shortages have increased the cost of pet care.

The Globe and Mail covered the ‘why’ in their article Why owning a dog or cat in Canada has become so expensive. As outlined in the article, the reasoning is truly a complex web of pre- and post-pandemic factors all pushing against each other in the worst ways possible:

With interest rates low, private equity firms were buying veterinary clinics for up to 30-times the clinics annual earnings. But now that interest rates have risen, companies are feeling pressure to raise prices to recoup their investment quicker

An increase in pet adoptions through the pandemic, coupled with veterinarian shortages are creating a textbook supply-and-demand problem where there is more demand on services than supply

Manufacturing issues are driving up the costs of drugs and food, increases that are passed on to pet owners

Since these conditions are not completely unique to the veterinary industry, many families are also feeling financial pressure in other areas and changing the way they care for their pets. The impact of these rising costs were outlined in Today’s Veterinary Business article When caring costs more:

Fewer visits: In 2023, clients spent more each time they visited the vet, but went 1.5 fewer times on average than in 2022.

Increased demand for subsidized services: Low cost or subsidized clinics are seeing more clients than ever before

Lower rate of adoption: more pets are entering shelters, and fewer are being adopted. Adoptions were down 9% from 2022 to 2023.

The article recommends a few steps veterinary practices can take to address this economic reality of the moment:

Veterinarians should be the ones responsible for conversations about cost. This eliminates back and forth with staff who need to lower estimates or change treatment plans. In doing so, vets should provide some indication of the approximate cost of care to provide a reference point for clients.

Be direct, empathetic and inclusive. Involve clients as part of the care team.

Offer various treatment and diagnostic options

Slow down on technology adoption. Increasing technology in a practice drives up cost to cover those associated with technical adoption

Prioritize tests based on budget.

When considering price increases be mindful of the community you serve, the cost of other essential services impacting family budgets, clinic visit data, and areas for practice growth

This is a tough situation and the suggested steps in the article don’t fully sit right with us. It’s hard to ask veterinarians to slow down on adopting technology in their practice when such technologies might be exactly what is needed for associate retention and reducing burnout. Additionally, while the cost of care is challenging, pet parents still have high expectations of their veterinarians and expect the best possible care. Being unable to offer that based on available resources may put a veterinarian in a difficult position. Ultimately, in the current economic climate veterinary practices need to balance their practice needs with those of their clients. There is no single catch all solution.

We are interested in hearing from you. What are you seeing in your practice as it relates to the cost of care? What steps are you taking to address this challenge? Hit reply to let us know and we may feature some of our favorite answers in next week’s edition.

👀

See what animals see

We’ve known for a while that humans can only see a limited range of light, due to photoreceptors in the eye that detect red, green and blue wavelengths. This spectrum, from 380 to 700 nanometers, is what we call “visible light.” But some animals including birds, honeybees, reptiles and certain fish can see light with even higher frequencies, like ultraviolet (UV).

But a new study published in PLOS Biology uses new video recording and analysis techniques to better understand how the world looks through the eyes of other species.

Researchers used a portable 3D printed enclosure containing a beam splitter that separates light into UV and the human-visible spectrum. The two streams are captured by two different cameras built to capture those wavelengths, and then the two video feeds are matched to produce a version of the footage that is representative of different animals’ color views.

But no matter the technique, we still can’t see the UV light whether it is organic or captured on video and enhanced. So although the results are merely approximations of what these animals are seeing, it is valuable work already providing some interesting findings: the startle display of a black swallowtail caterpillar has hornlike defence appendages that are UV-reflective, and peacock feathers rotating under a light appear even more vibrant to fellow birds than they are to humans.

If nothing else, the results are beautiful and worth one minute of your time:

🦇

Put up the bat signal

Last week, a bat interrupted a San Antonio Spurs NBA basketball game by flying around the court and distracting players. But within minutes, the game was back on after Spurs mascot, The Coyote, dressed up as Batman and captured the intruder. Which raised a few questions for us: how often does this happen that the mascot had a Batman suit ready and has been trained on what to do in this instance? And if they are such a common occurrence, what steps have been taken to reduce exposure and promote safe interaction between bats and sports fans?

In 2009, a similar instance stopped the game before Spurs point guard Manu Ginobili famously swatted it down with his bare hand. Which raised other questions like, did he receive post-exposure prophylaxis? The TV announcer mentioned vaccinations, but it appears like Ginobili simply continued to play in the game.

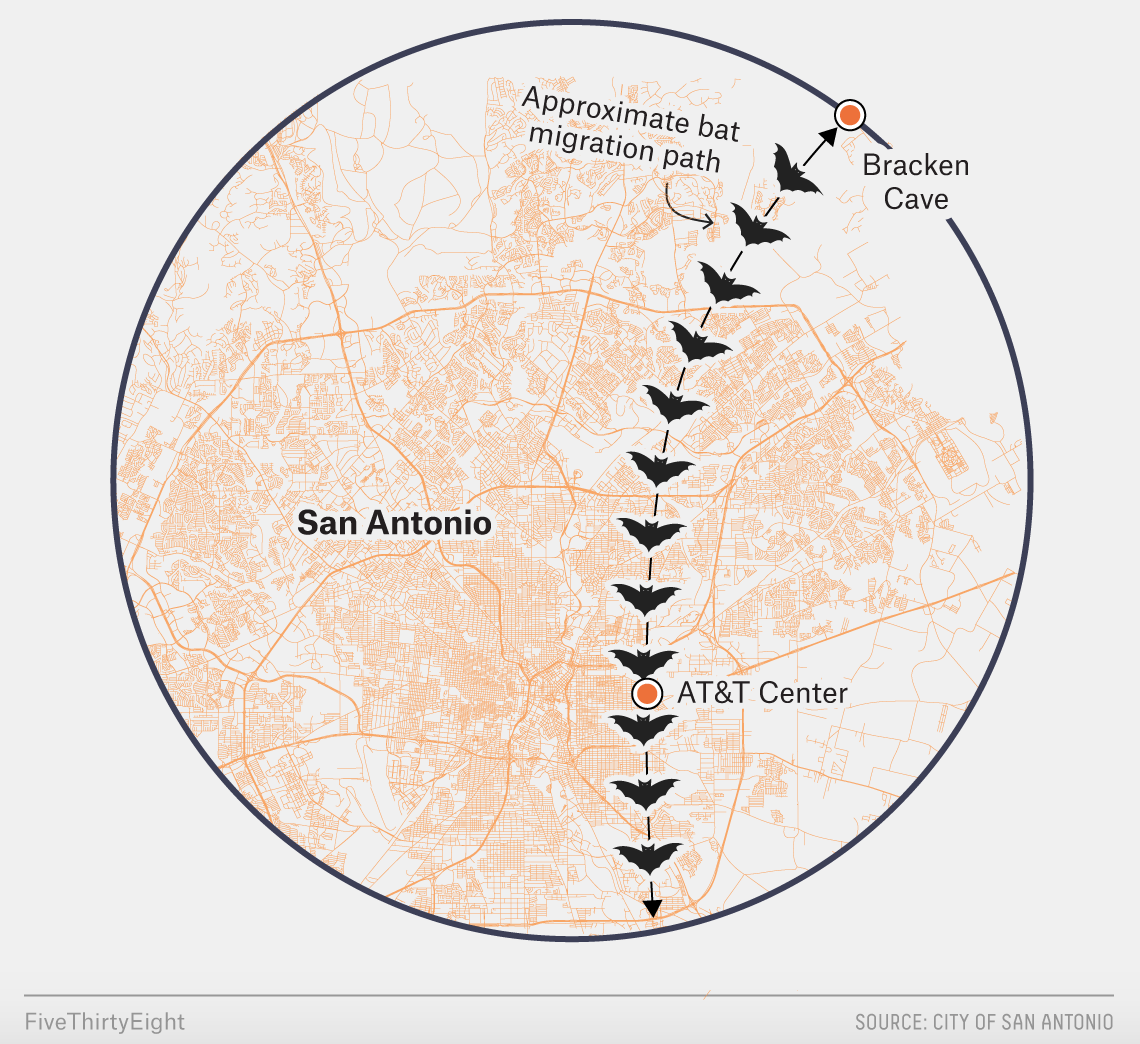

We did a bit of digging, and thanks to the fine folks at FiveThirtyEight, we have an answer as to the why: the arena is just 25 miles from Bracken Cave, the largest summer bat colony in the world, and 75 miles from the world’s largest urban bat colony. Plus, the arena is almost directly in the bats’ migration path from Central America and Mexico back to Bracken Cave, where maternal colonies fly to nurse their newborns.

Courtesy of FiveThirtyEight

It sounds like we’re a bit late to the news cycle, so you may have known this already, but we still can’t figure out why no one is talking about the possible rabies exposure, and health risks this poses to fans and players.

Instead of promoting the safety of humans and bats alike, SBNation is covering things like whether or not NBA stars would get superpowers from a bat bite and which ones are afraid of bats.

🚀

Quick Hits

Here are some of the other stories that caught our eye and we're following this week from around the veterinary world and animal kingdom:

Instinct Science Acquires Clinician’s Brief Owner, VetMedux [Globe News Wire]

Vetspacito: Helping pets and overcoming language barriers [AAHA]

Lawmakers Urged to Support Dog Importation and Rural Veterinary Shortage Legislation [Farm Journal]

Confusion around first legal FIP treatment in United States [VIN]

Michigan survey finds no new pathogen in CIRD cases [Detroit News]

Dog size may not link to cancer risk [ABC News]