Hello 👋

Welcome back to another edition of Weekend Rounds!

We hope you survived the 4th with all your fingers intact and that your dog has stopped shaking from all the fireworks. The summer may be slow for some, but its action packed over here.

For this week at least… because your favourite veterinary newsletter is going on a 2 week vacation. Unless something earthshattering happens we will be back in your inbox on July 26.

Here’s what we’re covering:

🦠 The future of veterinary oncology

📊 AVMA Chart of the Month

🐰 How to adopt a lab animal

🚀 Quick hits

🦠

The Future of Veterinary Oncology

This week, Today’s Veterinary Practice leads our weekly synopsis, with a deep dive into the future of veterinary oncology. As TVP reported, over the past two decades the veterinary oncology market has expanded significantly, driven by rising cancer rates in pets, improved preventive care, and increasing owner demand for advanced treatment. The number of ACVIM-boarded veterinary oncologists has grown from just 16 in 1990 to over 600 in 2024. Yet, demand continues to outpace supply, with more than 100 job openings across North America and only 35–40 new diplomates certified annually. Corporatization—now encompassing about 75% of specialty practices—has intensified competition for oncologists and pushed salaries higher, making it harder for academic institutions to recruit and train the next generation of specialists.

Despite the growing need, veterinary oncology remains a largely self-pay market. Only 3.7% of pets in the U.S. are insured, limiting access to care for many owners. Treatment costs often range from $5,000 to $15,000, and nearly 83% of oncologists cite cost as the main barrier to care. Prices have climbed due to inflation, advanced diagnostics, and increasing use of FDA-approved veterinary-specific therapies. Over the past two decades, veterinary care costs have more than doubled, further straining client budgets.

Market dynamics also complicate growth. Many practices rely on human generic drugs, which offer better margins but limit adoption of newer, more expensive options. Developing veterinary-specific cancer drugs is costly and slow, often taking over six years and $22 million—challenging feasibility in a price-sensitive, self-pay environment. Traditional markup pricing also doesn’t always work well for high-cost therapeutics.

To ensure a sustainable future, the profession must broaden access and affordability. This includes offering a spectrum of care options aligned with client needs and empowering primary care veterinarians to manage more cancer cases with safe, affordable treatments. Expanding training pathways—particularly in private and corporate settings—can help grow the oncology workforce. Greater pet insurance adoption and innovative pricing strategies will also be critical.

Most pets with cancer will never see a specialist. A sustainable path forward will require shifting the model to support both general practitioners and clients, ensuring pets receive compassionate, appropriate oncology care regardless of geography or income.

If you need a refresher on Oncology in your practice, Dr. Chris Pinard has an outstanding Obi course with 3 jam packed hours including what you need to know about chemotherapy types, surgical principles, adjunctive therapies, common tumor types in dogs and cats, prognosis, therapies and more

📊

AVMA Chart of the Month

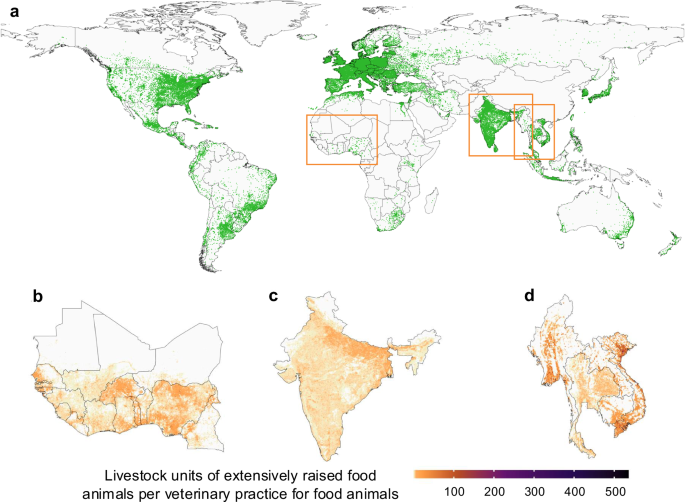

A recent AVMA report on the Economic State of the Veterinary Profession highlights how staffing ratios between veterinarians and nonveterinarian team members vary across practice types and how these differences can affect productivity and patient care. In 2024, companion animal practices had the highest average ratio of nearly 4 full-time equivalent (FTE) nonveterinarian staff per veterinarian, while food animal practices had a significantly lower ratio of 0.7. The report also found that veterinary technicians were more prevalent in companion animal practices than in equine or food animal practices.

These differences in staffing levels reflect the operational needs of each practice type. Companion animal clinics often operate from fixed locations, allowing them to support more staff, while equine and food animal practices tend to rely on mobile, independent work by veterinarians. As a result, the staffing models are adapted to the service delivery methods typical of each field. Practices with higher ratios may enjoy better support but must also watch for potential inefficiencies or blurred role responsibilities.

By calculating and comparing their own staffing ratios with AVMA benchmarks, veterinary practices can make informed, strategic decisions to enhance workflow, reduce burnout, and improve patient care. Whether a practice finds its ratios higher or lower than average, such data can reveal opportunities for adjustments in team structure, scheduling, or task delegation. Ultimately, refining these ratios—especially with seasonal fluctuations in mind—can lead to a smoother, more effective operation that benefits both clients and veterinary teams.

🐰

How to adopt a lab animal

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has launched an adoption campaign to rehome lab animals such as zebrafish and rats, following drastic funding cuts initiated during the Trump administration.

And yes, the absurdity of the situation is hard to overstate: instead of advancing science to better understand environmental pollutants, EPA researchers are now spending their time coordinating animal adoptions.

These cuts have targeted the EPA’s Office of Research and Development—its core scientific research division—slashing staffing and replacing it with a smaller office focused only on short-term, legally mandated projects. The decision has sparked outrage among scientists and watchdog groups. With the fate of over 1,000 EPA scientists hanging in legal limbo, the agency has now resorted to encouraging staff and the public to “Adopt love. Save a life,” instead of conducting foundational toxicology research essential for public health.

This shift away from rigorous, long-term research not only compromises the agency’s ability to assess complex chemical risks—like PFAS and microplastics—but also increases reliance on potentially biased studies from chemical companies. With the loss of critical animal models, such as zebrafish used to study neurological and endocrine effects of pollutants, the EPA is dismantling its own scientific infrastructure. This retreat from science may save money in the short term but comes at the cost of long-term public and environmental health.

🚀

Quick Hits

Here are some of the other stories that caught our eye and we're following this week from around the veterinary world and animal kingdom: